“Once the glamour girl, all legs and short skirts and long painted nails; once a fixture in the gossip columns which linked her to one attractive man after another, she has managed to transform herself almost totally.”

Nora Ephron wrote this about Gloria Steinem in an essay titled “Miami,” following the National Women’s Political Caucus at the 1972 Democratic Convention in Miami. It’s a memory of the feminist icon that many of us might not remember. Myself included.

I’ll admit that the best education I got about the women’s movement of the ‘70s came from Crazy Salad, Ephron’s collection of essays that includes “Miami.” That was where I learned about what it might feel like if you couldn’t trust your gynecologist to diagnose you with care and professionalism. If, as a woman, it was a default assumption that your doctor wouldn’t take you seriously.

It was where I learned how polarizing Steinem’s ideas were to the feminists who came before her; and where I learned of the deep divides between women who wanted to have jobs and women who wanted to stay at home with kids—that there was no conversation at all about “having it all” at that time, because it was a laughable idea when a career out in the world (accompanied by respect and the ability to climb a corporate ladder) was so hard-won that it required singular focus and all of a woman’s energy.

Thinking about the power and opportunity women have in today’s world, a lot has changed. Some things haven’t. And a few things have gotten worse.

In “Miami,” Ephron goes on in her description of Steinem, to say: “She has become dedicated in a way that is a little frightening and almost awe-inspiring; she is demanding to be taken seriously—and it is the one demand her detractors, who prefer to lump her in with all the other radical-chic beautiful people, cannot bear to grant her.”

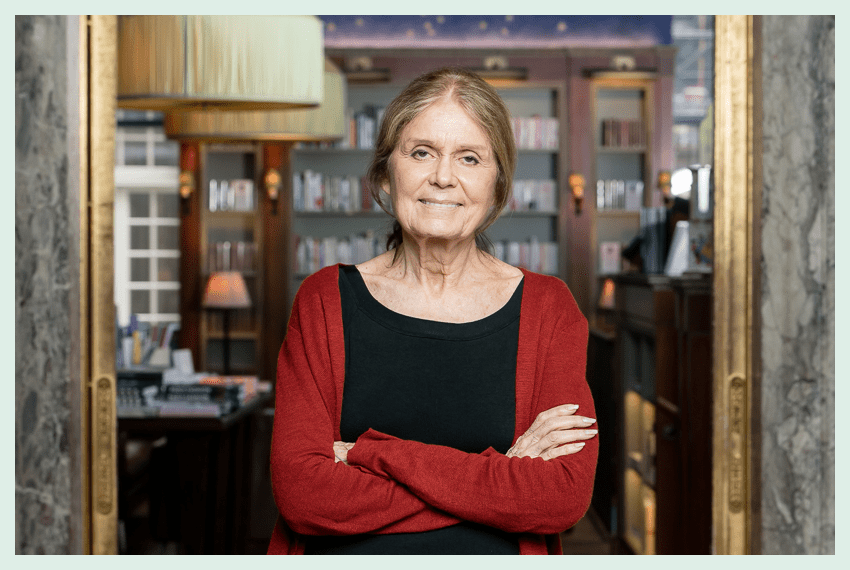

Today, at 83, Steinem may not have to fight quite as hard to be taken seriously. A lifetime of outspoken activism has won her that right in most circles. But she is as unyielding and dedicated and awe-inspiring as ever, in her efforts to unwind sexism and advance the message of feminism. And she isn’t precious about the ways in which that message is advanced. Asked about celebrity endorsements of feminism, and whether she sees them as valuable or shallow, she says, “We need to put the message in all the mediums. Whatever the medium may be.”

This upcoming month, she is working alongside poet, author, and activist Robin Morgan to curate the Albertine Festival in NYC. Featuring discussions with American and French feminist thought leaders—from Roxane Gay and Mona Chollet discussing the experience and representation of the female body; to a conversation on the politics of language, moderated to Steinem; to a vision of what a truly equal future might look like, featuring Cecile Richards, Caroline De Haas, and more—the festival is dedicated to feminism and to creating a space for legitimate dialogue between female thinkers, leaders, and artists.

“We didn’t have the phrase sexual harassment until I was in my 40s—it was just called ‘life.’”—Gloria Steinem

Bénédicte de Montlaur, cultural counselor of the US French Embassy, says they chose this theme because “we felt that feminism was a very important and vibrant issue, with a lot of movement and organizing happening in both France and the U.S. right now. The goal was to get a transatlantic conversation going.”

We had the opportunity to start the conversation on Girlboss, with both Steinem and de Montlaur. Read on for excerpts from our discussion, including a frank comparison of Harvey Weinstein and Donald Trump, as well as a thoughtful look at how women and men both “become whole” through feminism—and why men have the most to gain from it.

Q:

What’s the ultimate goal of this festival? Why are you bringing these particular women together now?

A:

de Montlaur:We are working with two of the curators we are dreaming of meeting. We year we really wanted to meet Gloria. But we also felt that feminism was a very important and vibrant issue, with a lot of movement and organizing happening in both France and the US. The goal was to get a transatlantic conversation going.

Steinem: It’s an opportunity to continue the feminist dialogue that has always gone back and forth between our two countries. And to do it in a very personal way. So we’re in a room together, getting to know each other, learning from each other. We’re making this experience possible for a wide variety of people over the course of all of these different events.

Q:

This festival is all about bringing women together to discuss problems and propose solutions. But there is a whole other subset of popular feminism that’s just about claiming the word and not much more. Is that kind of celebrity feminism valuable?

A:

Steinem:We need to put the message into all the mediums. Whatever the medium may be. Whether it’s the way we treat each other on a daily basis or the books we write or the way we raise our children, or the meetings we have. There are some basic rules we can use in all of these endeavors.

“Since language carries our dreams, we have to expand language to accommodate bigger dreams.”—Gloria Steinem

For instance, we can just remember if we are in a more powerful position than those around us, we can remember to listen as much as we talk. And if we have less power, we can remember to talk as much as we listen. Which may be difficult because we are accustomed to hiding. But just, some basic, obvious balance and democracy, and considering ourselves as a circle, not a hierarchy, in our everyday ways.

Q:

Gloria, you’re moderating a conversation about the politics of language. Why was that topic the most interesting to you?

A:

Steinem:As a writer, of course, probably both you and I are obsessed with language. It carries our meaning, and when we expand the meaning we expand the possibilities. So, even something as simple as saying “humankind” instead of “mankind” has been demonstrated to democratize people’s vision.

Q:

You speak a lot about the shared female activism in both France and the US. But you also note that neither country has ever had a female head of state. Why do you think that is?

A:

Steinem: Well, the universal reason, not just in our two countries, but wherever there is patriarchy, is the idea that men are leaders in public life and a woman’s proper role is only in private life. This has resulted in women raising children way more than men do. Therefore female authority is thought to be appropriate only in childhood, not to public life. We, in our different ways, are still dealing with this. So, men, and some women too, may look at a powerful woman and feel that this is not appropriate in public life because it makes us feel regressed to childhood, the only other time we experience powerful women.

The one other deep change goes along with this is physical change. And we are dealing with this. France is certainly ahead of the United States in both women and men raising children and women having the ability to have childcare and government assistance. The US government behaves as if children were born when they were six! They aren’t helpful in terms of universal childcare. In France, it’s not perfect, but it’s much more likely to exist.

“When you say “mankind,” we do indeed see men. When you say “humankind” we see everybody.”—Gloria Steinem

de Montlaur: In France, if you want to work and you have three kids, it’s really possible. And that’s a very basic but true different. I think one of the things that Gloria said earlier today was maybe you have more thinkers and prominent feminists in America because you have this problem of very little political representation and patriarchy. So you have something to resist against.

Q:

How do you think about emotional labor and mental load, in that same context? Is that an issue in France as much as it is in the US?

A:

Steinem: It’s an issue everywhere. For instance, it was treated as a great step forward, when a third of people shopping in supermarkets in the United States were men. But it turned out that 80 percent of them were shopping with lists prepared by their wives.

de Montlaur:In France it’s called the charge mental, and there is a very famous comic by a French artist about it. But yeah, there is a debate. And France is not a paradise at all on this topic because we are still very patriarchal. Because the ideal French woman, she’s supposed to do it all.

“Maybe you have more prominent feminists in America because you have this problem of very little political representation. You have something to resist against.”—Bénédicte de Montlaur

Steinem:Well, the idea of progress is that women take on more work rather than less work. I do think we need to state it in a different way though: Women become whole people by being active in the world outside the home, which allows us to develop all those qualities normally thought of as masculine, but are just human.

And men become whole people by being raised to raise children, at least, and perhaps actually raising children, which causes them to develop all the qualities normally called feminine, but are really human. That is patience, attention to detail, empathy, and flexibility, which men have to learn to gain their whole human selves. That’s why they have everything to gain by this change.

Q:

And what about when women experience harassment out of the home? How do you think about the slew of sexual harassment and assault allegations coming out against Harvey Weinstein?

A:

Steinem: It’s clearly progress to recognize the problem. We didn’t have the phrase “sexual harassment” until I was in my 40s—before that, it was just called “life.” To have the phrase, to have, in this country, Catherine MacKinnon, who was the architect of the law that turned sexual harassment into a legal offense, and the first women who brought those cases. There has been great progress. And with each revelation, we realize how prevalent it really is. Part of curing a disease is diagnosing a disease. And that is what we have been doing.

de Montlaur:And I think one of the areas where America was much more advanced than France was talking about sexual harassment and the level of tolerance. For a long time in France we were making fun of the American who couldn’t cope with compliments—which in fact were not appropriate—I think we’ve learned a lot from America on this subject.

“Our president is the harasser of women, and he was elected by a third of the country despite that.”—Gloria Steinem

Steinem: I think the current coverage shows two things. One: When one woman speaks up, it turns out that there are many others who have had the same experience and will come forward. So the truth is revealing itself. And also, the response to it has been to take [these accusations] very seriously. Very seriously. Harvey Weinstein, who is the creator of a film company has now been fired by his board.

But we should also remember that at the same time as we are seeing serious coverage of this problem, we have a problem in the White House. That he, the president, is the harasser of women, and that he was elected by a third of the country despite that.

Q:

What do you say to women who feel dejected by that fact? That all those people felt comfortable putting a known harasser of women into the White House?

A:

Steinem: Wait a minute. Hillary Clinton got 3 million more votes than he did. Plus, 7 million people who voted for candidates other than either one of them. He lost the election by popular vote. He utterly lost the election. Jack Kennedy was elected by a margin of less than a thousand vote. [Trump] lost by 10 million.

But there are two problems here. One, that too few people voted, which is fundamental. But also, that we have to get rid of the electoral college, which is the antithesis of one person, one vote.

If only women in this country had voted, he would not be president.

This story was originally published on October 18, 2017. It has been updated (and will continue to be updated) to include new tips, advice, and guidance, to ensure we are always giving you the best, most valuable resources.